On a lovely but chilly May morning I arrived at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore and saw this marvelous mountain of sand that begged to be climbed.

I was glad it was chilly because the Dune Climb is steep, and, well, sand is a bitch to walk thru. Once at the top, there is a dune trail is marked by posts and levels out somewhat.

It’s about 3 miles to the lake, and I believe I went about a mile and a half before thinking I didn’t want to be too tired to get back.

I found the traverses down and back up the dunes to be brutal. And not knowing what I was getting into, I hadn’t brought any water (always take water!). But what a place!

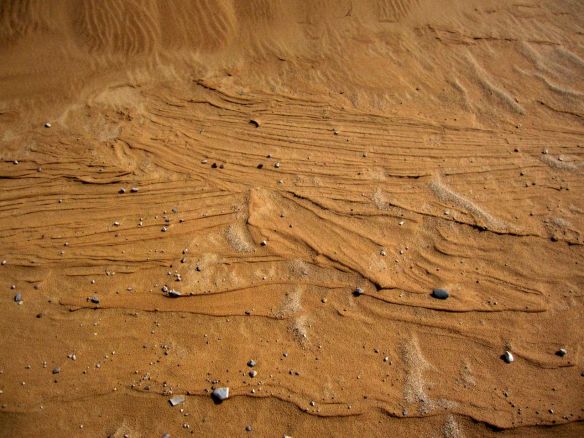

Grasses, especially beachgrass, grab any opportunity to thrive; they slow the wind, making deeper sand downwind. The increased sand load can then bury neighboring plants. But in windy corridors (or along trails), plants can’t get established, and the sand and wind express themselves in complex ripples.

Here’s how I understand the formation of the dunes at Sleeping Bear. The last ice age delivered vast moraines of sand and gravel to Michigan. The glaciers were pretty much gone by 8,000 years ago, and as the ice load came off, the land rose (“isostatic rebound”), and blocked the North Bay drainage pathway to the east through what is now Lake Huron. The new drainage pattern created the Lake Nipissing Great lakes, with a proto-Lake Michigan. With lots of sand, and wildly fluctuating water levels, prevailing winds from the West began building the dunes we see today. These are called “perched dunes”; old, high dunes made of sand deposited on top of glacial moraine. The highest elevation of the dunes, Sleeping Bear dune itself, is about 450 feet above Lake Michigan, but the sand is not that thick. The park also has plenty of lake-level beach dunes

The sand itself comes from glacial deposits near the lake shore, or that have washed into the lake from inland deposits. Then during periods of relative low water, the sand is blown on shore by prevailing winds.

About a mile from the parking lot there’s a notch between the dunes.

The formation is probably encouraged or created by by trail erosion, but it has beautifully exposed layers of sand showing bedding and cross bedding structures.

I found this area oddly exciting, like seeing sandstone come alive in these delicately patterned layers of sand. The structures are fragile.

What preserves the distinction between layers? The sand is pretty thoroughly unconsolidated, but apparently there is already enough structural variation between layers for them to erode at different rates. Presumably layers represent episodes of various wind

conditions; the cross bedding occurs on the lee side of the dune with the maximum slope corresponding to the wind direction. This was bothering me, so I consulted Arthur L. Bloom’s Geomorphology – Systematic Analysis of Cenozoic Landforms, which has a really good discussion of aeolian processes. The threshold velocity for erosion is related to grain size, so the layering reflects sorting during deposition.

The gravel is “lag” gravel, and is left behind as sand blows away. Still a bit curious that there’s so much of it this high, about 300 feet above the lake, and pretty much local high ground.

The Sleeping Bear Dunes Website has a website at http://www.nps.gov/slbe/index.htm and good geology field notes at http://www.nature.nps.gov/geology/parks/slbe/; there’s also a good explanation of ancient shorelines of the Great Lakes at http://www.nps.gov/piro/naturescience/upload/August_2009_PIRO_Resource_Report_Blewett.pdf Also, I’ve learned much from Raymond Siever’s Sand, a Scientific American Library mongraph that is about a lot more than just sand.

Great blog. Your photos and explanations are well done. Really gives a flavor for the area (except for the size of the dunes of course).